|

|

“We don't know if women think differently than men, and we may not know it for a long time," architect Denise Scott Brown, at a July conference in Istanbul.

Are there fundamental differences in the way the two sexes see? As women increasingly find their way to becoming full partners in the structures of society - including architecture - will they make things better, or just rearrange the deck chairs? (And as you judge this article, keep in mind that Lynn isn't just a girl's name)

Those questions form the subtext of Five Architects, a new exhibit at the Chicago Architecture Foundation that runs through November 20th. Designed by Gensler's Elva Rubio, Five Architects uses still images and videos to document Midwest projects from five women architects. It invites us to explore the consequence of gender not just in how designs are made, but also in how architecture is depicted and perceived, and, ultimately, in how it relates to the structures of power.

There's no question but that those structures have historically been monopolized by men, and that the results, including in architecture, have been a decidedly mixed bag. There's a school of thought, articulated by philosopher Mark C. Taylor, who lectured at MCA and IIT earlier this year, that the severe geometry of an architect such as Mies van der Rohe, as expressed in such designs as Chicago's IBM Building or Federal Center, where right-angles rule and curves are banished, represents a controlling, perhaps even totalitarian world view that shoehorns reality into a forced, debilitating grid. Freedom in Mies' buildings comes from their open, “universal” space, not from the forms the buildings take.

Taylor cites French architect LeCorbusier's belief that geometry was the foundation of our world, and the means by which we experience and express it, an idea that stretches back to the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome. In the first century B.C., the architect Vitruvius related the story of how the mood of a shipwrecked Greek philosopher brightened upon discovering geometrical figures drawn in the sand, “Let us be of good cheer,” he said, “for I see the traces of man.”

LeCorbu was more polemical: “Man walks in a straight line because he has a goal and knows where he is going.” He contrasts man to a pack-donkey, who “meanders along, meditates a little in his scatterbrained and distracted fashion.” As Taylor describes how LeCorbu saw his brave new world, the “messy” is supplanted by the “exact”, the “accidental” by the “essential,” “body” by “mind”; and “feeling” by “reason.” LeCorbu found the curve “ruinous, difficult and dangerous, it is a paralyzing thing.” So many of the traits he damns are clichés of “feminine” attributes. Was LeCorbu the ultimate male sexist pig?

Zaha Hadid, one of the new exhibition's five architects, is an official dropout from LeCorbu's right-angles- rule-school. “There are 359 other degrees,” she has said. “Why limit yourself to one?" Taylor sees her kind of architecture as our liberation from repressive simplification, but uses a guy, architect Frank Gehry, as his example. Gehry's Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park, with its infinitely curving forms, is like an architectural improv, a direct blasphemy against LeCorbu's commandments. rule-school. “There are 359 other degrees,” she has said. “Why limit yourself to one?" Taylor sees her kind of architecture as our liberation from repressive simplification, but uses a guy, architect Frank Gehry, as his example. Gehry's Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park, with its infinitely curving forms, is like an architectural improv, a direct blasphemy against LeCorbu's commandments.

To Jeanne Gang, the Chicago architect whose SOS Children's Village Community Center is another of the projects featured in the exhibition, this kind of flux is not negative, but enabling. “It has to do with feminist thought,” Gang has said, “where a fluctuating, changing identity is something that is very against the singular . . . the kind of perception of  there's one, there's a oneness. The philosophical framework of feminism . . . is looking at things from these perimeter positions - not the center of power position, but from this condition where you're on the margins. And so you have a different way of looking. When we make form, we're thinking about how can we make the identity fluctuate, it doesn't have to be one thing all the time.” there's one, there's a oneness. The philosophical framework of feminism . . . is looking at things from these perimeter positions - not the center of power position, but from this condition where you're on the margins. And so you have a different way of looking. When we make form, we're thinking about how can we make the identity fluctuate, it doesn't have to be one thing all the time.”

American architecture developed as a men-only enclave. The first women to graduate from MIT's architecture program was 23-year-old Chicagoan Sophia Hayden. She was unable to find work until winning a competition to design the spacious, majestic Women's Building at the 1893 Worlds Columbia Exposition. She was paid a fraction of what the fair's other architects got. The critics - another old boy's club - condescendingly remarked on the buildings feminine qualities such as its daintiness and grace. In the year before the fair, Hayden fell ill - “brain fever” they called it - and while she would live another sixty years, she never got the chance to build again.

The second woman to graduate from MIT, Marion Mahony, was made of sterner stuff. She was Frank Lloyd Wright's first employee, and perfected the distinctive rendering style that would help make his architecture famous throughout the world. She later collaborated with her husband, Walter Burley Griffin, to win a competition to design Australia's new capitol city of Canberra, but her work became lost in the shadow of her two male colleagues. Only now is that situation being redressed, and an exhibition of Mahony's work Marion Mahony Griffin: Drawing the Form of Nature is on display at Evanston's Block Museum through December 4th.

"At the highest levels of our profession, sexism is still rampant," says Denise Scott Brown, but today you can see the cracks coursing through the surface of the glass ceiling. In Chicago, hundreds of women are active in the profession, and the best of them are doing more to reinvigorate Chicago's architectural tradition than most of their more moneyed male counterparts. Chicago's architectural godfather, Stanley Tigerman, puts it plainly: “Jeanne Gang is a god-damn good architect. Period. I have no qualifiers on it. She's real Chicago, which means it's about structure and construction. It's not just the arbitrariness of design.”

So why, then, do we need an all-girls show like Five Architects? The title references a book of the same name from 1972, which featured the work of five architects (all male) including Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves as they tried to define themselves as an emerging school. That was thirty years ago, and at first glance, it seems a step backwards to be segregating work by gender. Is Five Architects an exercise in empowerment, or marginalization?

Five Architects: the Exhibition

First impressions aren't exactly reassuring. Stuck in a corner of Daniel Burnham's two-story, classical Santa Fe building  atrium, Five Architects seems almost engulfed by the vast space that Chicago Architecture Foundation shows usually cram full with display boards and models. And if your first stop at the exhibit is the video on Jeanne Gang's SOS Center, you may even more unimpressed. Gang's project has the disadvantage of not breaking ground until next month, so the video begins with a lot shots of people starring into video monitors, and of architects having discussions, which gets old very quickly, especially since you can't hear anything that's being said - all the videos are presented without sound. “Acoustics in that space (are) very difficult,” explains Rubio. atrium, Five Architects seems almost engulfed by the vast space that Chicago Architecture Foundation shows usually cram full with display boards and models. And if your first stop at the exhibit is the video on Jeanne Gang's SOS Center, you may even more unimpressed. Gang's project has the disadvantage of not breaking ground until next month, so the video begins with a lot shots of people starring into video monitors, and of architects having discussions, which gets old very quickly, especially since you can't hear anything that's being said - all the videos are presented without sound. “Acoustics in that space (are) very difficult,” explains Rubio.

But hang in there a second. The best way to understand Gang's project is to go to Five Architects' other primary component - a simple, long, table-like stand with five, identically formatted, large-scaled portfolios whose plasticized pages contain floor plans, renderings, photos and descriptions for each project. Usually this kind of stuff is mounted on large board or big freestanding walls. When done well, these can be artistic objects in themselves, especially when they're scaled generously enough to convey the scale and sense of a project. Viewing them, however, is often a real pain. How many times have you gone to a show and had a hard time finding the right place to stand, especially to read the text - frequently placed too high or too low? The no-frills simplicity of the Five Architects portfolios keeps the buildings - not the presentation - as the primary focus.

Admittedly, this would make for an interesting, but rather dull show, but for its companion piece- five small monitors, each displaying a looping video on one of the projects, mounted flush in a high wall that's faced, as is the portfolio stand, in Newmat, a distinctive PVC membrane material, which Rubio says is “almost like skin. It's very elastic. It has memory and can be seam-welded so it can be stretched to a very large scale.” Push on the skin - gently, please - and it yields to your touch. Very anti-macho.

Since a second project, Sejima Kazuyo and Ryue Nishiuzawa's Glass Pavilion at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, won't open until next year, its video is an essay on the building's construction. It's best viewed after you look through its exhibition portfolio, since the video really fails to give you any clear idea of the pavilion's eventual form and purpose: housing 5,000 glass pieces, dating from ancient to contemporary times, in a unique structure that uses glass not only for the rounded-corner exterior walls but for interior dividers, many of which snake unabashedly through the building in sensuous pack-donkey curves. “The effect,” says Sejima, “is a complex visual interplay of transparency, reflection and refraction. The glass is transparent but there are so many curved layers that the building has an opaque feel to it.”

The other three videos are of completed projects, and the way they document them marks another break from male-generated tradition - where architecture is recorded less through photojournalism than through what, in the last analysis, is very much like a fashion shoot.

Presenting Architecture - The Perfect vs. the Dynamic

“People would say to me,” says Nick Merrick, “Nick, these pictures are lying . . . they're so heroic, so pristine that it's not the real experience of the building, and my response was (that) of the thousand of possible realities that you could have, I picked the best possible one.” Merrick would know. He's one of the best in the business, and president of Hedrich-Blessing, the firm that since 1929 has created some of most iconic images of modern architecture - from Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater to Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House, to Mies, himself, puffing on a cigar in Crown Hall. “Personally,” said Merrick, “I have consciously made an attempt to not shoot the heroic, big gesture photograph. It never appealed to me,” but he concedes, “We're commercial artists. They commission us to create those heroic images.”

Another thing typically omitted from such photographs is humanity.” “People are messy,” explains Merrick, adding, “In interior photography . . . the exposures can be one and two minutes long, so you can't even have a natural sense of a person unless they're posed. I'll use them occasionally for scale, as well as mannequins, but frankly, it would be easier for me just to bring a mannequin, sometimes.”

As much as the buildings themselves, the videos of Five Architects' three completed projects suggest a feminist response to the traditional (male?) single controlled point of view, both for experiencing a building and for photographing it. No one would mistake these videos for high art - they almost have the quality of a home movie - long, slow pans and zooms, with a weakness for pretty shots like a pipe cutter throwing off a shower of sparks. Rather than moving through the space, the camera is usually stationary, depending on the people moving through the shot to give it life. But each video has 20 to 30 separate shots - 30 different ways of looking at a building.

By adding people to the images, the videos provide add a measure of how the scale relates to human form. By seeing those people move through a building, you get a sense of the flow of energy through its spaces. Hadid's Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, on exhibit at Five Architects, is a jazzy stack of offset rectangular forms faced in concrete, glass or, in one case, a black matte finish aluminum. In official photos, it can seem a sleek but forbidding intersection of abstract forms, which is definitely not Hadid's intent. “Buildings can be fun, exciting places,” she has said, and that comes through in the video, in a shot of the heads of people bobbing happily along above the ebony matte sides of one the diagonal steel staircases - fabricated by a local roller coaster company - that unite the museum's galleries, happy campers in a serious work of architecture that's also playful and inviting.

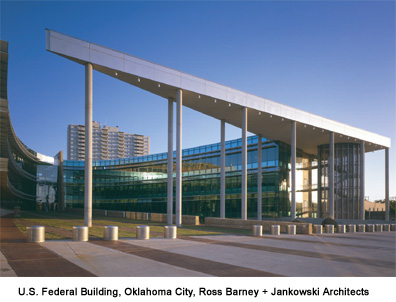

When you see an unpopulated photo of one of Mies's or Wright's totally controlled spaces, right down to the furniture and fabrics, you can't help but wonder if it's perfection would wither under the imposition of the human  form. When you see, in the video of Carol Ross Barney's Federal Campus in Oklahoma City, a great shot of an amply-shaped women dressed all in pink, standing like a brilliant wildflower against the careful earth-tone's of Ross Barney's interior, it's the kind of liberating rush you get when the plastic slip covers are finally pulled off the sofa. An architect like Ross Barney isn't afraid of that kind of complexity - her Federal Campus interior includes a skylight with dichroic fins in different colors that cast patches of a rainbow on a tan wall of coursed rock. form. When you see, in the video of Carol Ross Barney's Federal Campus in Oklahoma City, a great shot of an amply-shaped women dressed all in pink, standing like a brilliant wildflower against the careful earth-tone's of Ross Barney's interior, it's the kind of liberating rush you get when the plastic slip covers are finally pulled off the sofa. An architect like Ross Barney isn't afraid of that kind of complexity - her Federal Campus interior includes a skylight with dichroic fins in different colors that cast patches of a rainbow on a tan wall of coursed rock.

In the last analysis, you'll get a better idea of what may be different about female architects from these kind of details than from Five Architects' proclaimed theme of “diversity and collaboration”, in “deliberate contrast” to the “heroic modern tradition” that the male Five Architects tapped into in 1972. All of post-Miesian architecture is about breaking out of the straight-line box, but if you think women architects reinvented curves or color, you've obviously never seen a geodesic dome from Buckminster Fuller or Helmut Jahn's 1985 Thompson Center. In fact, the last entry in Five Architects, Julie Snow's Minneapolis light rail transit stations, is a reminder of just how elegant and powerful the old Miesian steel-framed transparency can be, especially when it's updated and enriched, as Snow does with colored glass panels.

“Collaboration” may be the watchword, and the internal workings of the five, women-led firms may well be freer and  more participatory their male counterparts but they all still sail under the brand of one, or at most two, individuals. Zaha Hadid has 60 people working for her, but there's no question but that her larger than life persona is the public face of her firm. She's notorious for hair-trigger explosions of temper, frequently targeted at her intensely loyal employees. She bristles at being referring to as a diva - "If a man talked and acted as I have, no one would say that of him," she has said. - but to suggest that she doesn't cultivate that image is disingenuous. While the other four portfolios in Five Architects use the end pages to dutifully list all the collaborators, usually with individual photos, Hadid's ends with a double-page spread almost entirely devoted to an extreme close-up, high-fashion portrait of the architect's admittedly fascinating visage. more participatory their male counterparts but they all still sail under the brand of one, or at most two, individuals. Zaha Hadid has 60 people working for her, but there's no question but that her larger than life persona is the public face of her firm. She's notorious for hair-trigger explosions of temper, frequently targeted at her intensely loyal employees. She bristles at being referring to as a diva - "If a man talked and acted as I have, no one would say that of him," she has said. - but to suggest that she doesn't cultivate that image is disingenuous. While the other four portfolios in Five Architects use the end pages to dutifully list all the collaborators, usually with individual photos, Hadid's ends with a double-page spread almost entirely devoted to an extreme close-up, high-fashion portrait of the architect's admittedly fascinating visage.

That kind of egotism usually sets off the alarm bells, but compared to an unabashed scoundrel like Wright (among his many adventures was abandoning his wife and children to run off with the wife of a client), Hadid seems a piker - her worst offense seems to be rudeness. Yet Hadid has obviously discovered that a high-voltage persona can sometimes get you places that sheer, raw talent cannot. Her wake-up call may have come in the 1990's, when she thought her career had been made as she won - twice - competitions to build a new opera house in Cardiff, Wales, and then watched a Lilliputian band of burghers headed by the brain-diapered Prince Charles chisel away at the project until its funding was switched to a rugby stadium. “People said,” Hadid told the Cincinnati Post, “'All you have to do is be nice,' because they believed in fair play. Well, I hate to say they were wrong. And I paid a very high price."

Last year, when a controversy briefly flared up as Jeanne Gang won a competition to design a visitor's center for the new Ford Calumet Environmental Center in Hegewisch, Stanley Tigerman counseled, “Jeanne's got to develop a thick skin.” Gang's response was as individual as her architecture; “Thick skin isn't a goal for me. Thick skin makes you insensitive - a bad thing. I can deal with a few cuts on my skin, because my strength comes from my core.” Adds Denise Scott Brown, “I believe we women architects should not drop our solidarity or our feminism -- we will need both in our careers."

Join a discussion on this story.

lynnbecker@lynnbecker.com

© Copyright

2005 Lynn Becker All rights

reserved.

|