Of the dozens of Chicago buildings designed by the fabled partnership of architects Daniel Burnham and his chief designer, John Wellborn Root, only a  paltry few survive today. Until recently, few would have imagined they included the unassuming, workday church at Broadway and Addison with its cheap white shingles and painted green trim. Alternations had so obscured obscured Root's original design that it led Donald Hoffman, Root's chronicler, to conclude that it “looked back to a Colonial type.

paltry few survive today. Until recently, few would have imagined they included the unassuming, workday church at Broadway and Addison with its cheap white shingles and painted green trim. Alternations had so obscured obscured Root's original design that it led Donald Hoffman, Root's chronicler, to conclude that it “looked back to a Colonial type.

”When the Lake View Presbyterian Church was built in 1887-88, it wasn't even in the city. “It was a woodland area,” says James Hall of Holabird & Root, the restoration architect on the project. “There was a commuter line that took you form the Loop to about this point . You jumped on another train, and went up to Evanston to your home. .” if it had been just a few blocks south, Chicago's strict post-fire building code probably would have prohibited the wooden church from even being built.

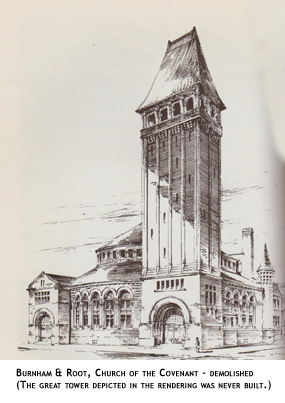

In buildings like the Rookery, Root drew on the brawny, Romanesque buildings of Boston architect H.H. Richardson, the Falstaffian-girthed architect from Boston. “They  corresponded with him. They were aware of him through publications,” said Hall during a recent lecture sponsored by the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects. “He was in town for the construction of the Marshall Field warehouse store,” a stunning rockpile that combined the modernity of great arched windows with a heavily rusticated façade - a palazzo for the wholesale trade. Root was clearly under Richardson's influence when he designed his similarly robust 1887 Church of the Covenant at Belden and Halsted, now demolished.

corresponded with him. They were aware of him through publications,” said Hall during a recent lecture sponsored by the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects. “He was in town for the construction of the Marshall Field warehouse store,” a stunning rockpile that combined the modernity of great arched windows with a heavily rusticated façade - a palazzo for the wholesale trade. Root was clearly under Richardson's influence when he designed his similarly robust 1887 Church of the Covenant at Belden and Halsted, now demolished.

“It's my suspicion,” says Hall of Lake View Presbyterian, “that the church may have been designed to be made out of masonry originally, just because of the massing, but the church never really had a lot of money . The entire construction and the site ended up costing $13-to $14,000 at that time, which even then was not a lot. And I think that Burnham and Root adjusted their vision of this place to a timber-framed, wood infill building with cedar shingles.”

In so doing, Root drew on another strain of the Richardsonian legacy, which came to known as the “shingle style,” ,” defined by critic Vincent Scully as comprising “natural and indigenous materials, simple construction, free adjustment of space to function and expression, and amplitude without pretension.”

Hall and his team found the church in a substantially diminished state. There were those  white shingles, “an abestos-containing cementicious shingle that was added round the mid 20th century. There were hanging gutters that were attached to the building that were not original. They were not sized correctly for the pitch of the roof and the amount of water they would receive. They would overflow all the time and were basically tearing the eave off the sides of the church. There was plastic sheeting covering the stained glass arched window over what is now known as the chapel of the church on the east side, and it was yellowing over time because of UV degradation.”

white shingles, “an abestos-containing cementicious shingle that was added round the mid 20th century. There were hanging gutters that were attached to the building that were not original. They were not sized correctly for the pitch of the roof and the amount of water they would receive. They would overflow all the time and were basically tearing the eave off the sides of the church. There was plastic sheeting covering the stained glass arched window over what is now known as the chapel of the church on the east side, and it was yellowing over time because of UV degradation.”

“The millwork for the arches were in bad shape,” says. Hall. “We were able to shop-fabricate an arch that we could install on site . . . a polymer-like material that's the only  non-natural material on the church.” They inserted loose-fill insulation in the walls to make the building more energy-efficient. They added “flashings to a building that never really had flashings,” to minimize future moisture-based damage. They deployed spiky nixalite barriers to discourage roosting, which had left a rather rancid residue in the church's bell tower. “They say Patagonia is where whales go to die,” says Hall. “I know where pigeons go to die. Right here.”

non-natural material on the church.” They inserted loose-fill insulation in the walls to make the building more energy-efficient. They added “flashings to a building that never really had flashings,” to minimize future moisture-based damage. They deployed spiky nixalite barriers to discourage roosting, which had left a rather rancid residue in the church's bell tower. “They say Patagonia is where whales go to die,” says Hall. “I know where pigeons go to die. Right here.”

Root wrote of “the right of color to be recognized as an independent art.” The church originally had a rich, warm palette, but rediscovering exactly what it was took a bit of detective work. Consultant Brent Humecki analyzed 60 old paint samples under a microscope - finding 12 to 14 different layers on some areas of the building -  and came up with a palette of five basic colors, from a brick red on the main body of the church and roof to a jute brown on the arches, windows, and doors. “We tried to do it as accurately as we could,” says Hall. “We were not really brought in to be preservationists. We looked at types of plastic shingles that could applied to fireproof the place, and just by showing the other options we had to our owner, they made the right decisions.”

and came up with a palette of five basic colors, from a brick red on the main body of the church and roof to a jute brown on the arches, windows, and doors. “We tried to do it as accurately as we could,” says Hall. “We were not really brought in to be preservationists. We looked at types of plastic shingles that could applied to fireproof the place, and just by showing the other options we had to our owner, they made the right decisions.”

Another major effort was replicating the striking original shingling scheme, everything from scallop-cut shingles under the pediment to spiraling shingles rising up the cone of the church's tall bell tower. Hall was quick to praise the work roofing contractor Knickerbocker Roofing. “These guys loved rising to the challenge of trying to replicate the craftsmanship that was done so many years ago.”

While pastor Joy Douglas Stromme was a stalwart supporter of the restoration, the congregations needs remained at the forefront - “We recognize this thing as a toolbox,” Halls remembers being told, “not as a jewel box.” Still, the final result is a revelation. The church has shed its derelict, tired skin, and revealed the warm beauty that had been buried within. It's not only a major increment to the Burnham & Root legacy, but an extraordinarily handsome reassertion of history into Chicago's contemporary urban fabric.